A Slow Tempo Exploration of Cuban Cuisine and Gastronomic Customs

Food, in its timeless essence, serves as a unifying force, bringing people together amidst the harshest struggles and the most joyous celebrations. With that said, I extend an invitation to savor small, deliberate sips and relish the glimpses of a cultural refreshment.

-S.C.

For many Americans, the notion of gathering as a family for nightly dinners remains just that—an idea. Ensnared within the relentless clutches of “9-5” schedules that extend well into the ungodly hours of the night, the pervasive work culture, and normalized rush of consumption have eroded and obliterated ancestral traditions of breaking fast together. Beyond the relentless work culture, there exists a steep price on the altar of convenience. Many people opt for the ease of ordering in through apps, thereby avoiding interactions with fellow human beings and sidestepping involvement in the art of food preparation. This allows individuals to seclude themselves within their solitary corners, seeking refuge from the monotony of daily life through the glow of a portable light-box.

In the following essay, my intention is to escort you through an exploration of a profoundly distinctive food culture—one marked by lengthy, leisurely meals designed to cultivate communal storytelling, the shared passing of food, and the commemoration of the day’s collective toil. Cuba, situated in the Caribbean, serves as a melting pot of flavors and influences. Rooted in West Africa, Spain, China, and its indigenous cultures–Ciboney, Taino, and Arawak, the island nation has forged a cuisine both familiar to other Caribbean, Latin, and even Southeast Asian countries, while simultaneously maintaining a distinct and well-preserved identity.

It is imperative to acknowledge that in today’s world, some of the intricacies of Cuba’s food culture and customs are tied to the challenges with their socialist government, compounded by external pressures hindering trade and globalization, such as the U.S. embargo. Sitting down and sharing meals with the locals allows one to gain profound insights not only into the culinary aspects but also the very essence of the people and their way of life.

Javi’s Breakfast

The notion that breakfast is the most important meal of the day has been debunked, attributed to lobby influence and the American bacon industry. Shifting the perspective to claim that a Cuban breakfast is the ideal way to start the day might hold more merit.

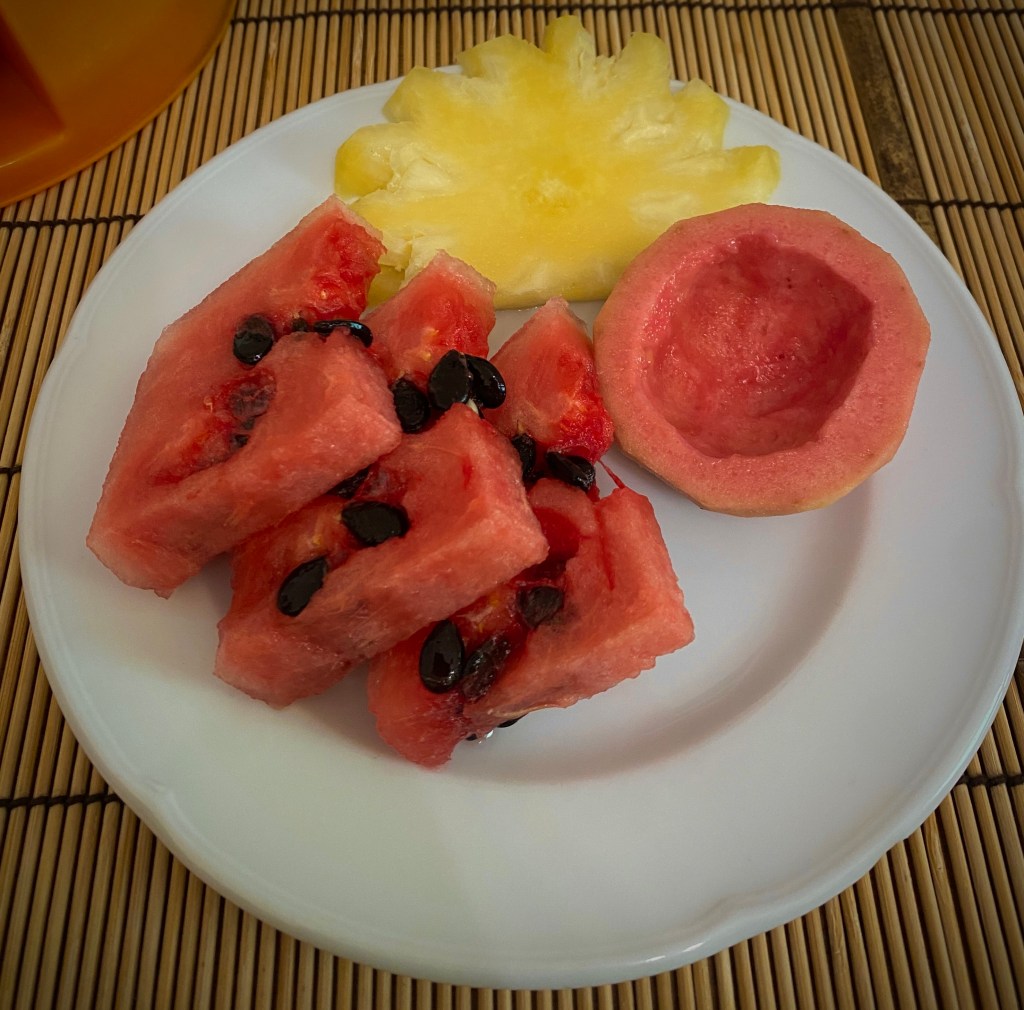

The first meal I enjoyed each day with my host family and housemates started with a plate of freshly cut fruit, followed by a hot starch and protein (eggs or meat), and an accompaniment of beverages, usually fresh fruit juice, water, and Cuban coffee.

I am personally unaccustomed to breakfast. During New England winters, I seldom consume fruit as there are limited seasonal options with my unfortunate allergy to citrus. The Cuban diet, marked by an abundance of fruit and a strong emphasis on three nutritious, balanced meals a day, was a refreshing culture shock for both myself and my peers. Taking time to eat, digest, and engage in morning conversation with our host family and housemates proved to be a very enriching, human experience. Unlike the usual on-the-go choices of energy drinks, extra large iced coffees, or highly processed pastries, we embraced the morning sun, engaging in mindful conversation while properly fueling our bodies for the day ahead.

Burnt Palms y Plátanos

A cooking lesson from my host mom.

Upon waking up from my 14-hour travel-induced slumber, I make an appearance with my host family, hoping to find a way to make myself useful. Despite my Los Angeles upbringing surrounded by Spanish, my conversational skills are limited, leaving me somewhat tongue-tied. My host mom communicates with me in Spanish, offering instructions that I can only catch every fourth word of. I pay attention to her gestures as she demonstrates a specific technique for dicing carrots. Once I finish the task, I notice she has moved on to frying disks of plantains.

She grabs a white plastic bag, places a freshly fried round on it, folds the bag over, presses the round flat with her palms, and then places the finished products onto her plate. Gesturing for me to try, my initial attempt is, to put it crudely, disastrous. Uneven pressure in the middle results in a lumpy, uneven mush with a crack down the middle. She laughs and communicates with me, and I nod as if I understand. Placing my less-than-perfect attempt on the plate, she says “buena.” With continued practice, I eventually get the hang of it, though barely keeping up with the rounds she continues to fry.

With every press, a hot sensation courses through my hands. Through the plastic, my host mom pulls my hand into hers, pointing out its redness and cautioning that I must wait or risk burning myself. I find myself a little embarrassed; her hands are used to the heat and the process, whereas mine are sensitive and slow to move. As I produce more flattened rounds, she fries them a second time and allows me to season the crispy golden goodness with flaky salt. While setting the table for dinner, my host father walks in, informing me that my host mom had set aside a few crisps for me to try. I take a bite of pure heaven.

While finding ways to help around the household, I realized how the act of food preparation is very universal. Despite my host mom and I not being able to speak more than a few words to each other in our respective native tongues, we were able to bond and laugh. I also appreciated the warm and open welcome I felt as a member of the family with the few contributions I made at mealtimes, such as setting the table, clearing plates, or helping to prepare a dish. Nothing was stressful or rushed about the food preparation, unlike what I am used to in the United States.

In Cuban cuisine, plantains, starchy fruits with a flavor profile between bananas and potatoes, are essential ingredients. From savory tostones, twice-fried green plantains (as shown in the video above), to sweet maduros, the versatile fruit plays a crucial role in various dishes, contributing texture and taste to the island’s flavor profile, shared with many other Caribbean and Latin American countries.

El palacio de Javi

Vedado, La Habana Province, Cuba

The simple kitchen that kept us students well fed.

Common Cuban Family Dinners

Slight difficulties in maintaining a good Wi-Fi connection turned out to be a blessing. We were unplugged from our devices, including during all meal times. Similar to breakfast, dinner was a time to eat slowly and recap our days. Served family-style, with large plates and portions passed around the table, the experience was refreshing due to the human connection it fostered. It’s challenging not to repeat myself, but the contrast in dinner culture between Cuba and the States is striking. In the States, dinner often feels rushed, reflecting the pervasive idea of being consumed by work throughout the day. Many people resort to convenient and fast takeout, microwave meals, and end up eating alone. The question arises: How can one face the next day with a pitiful culmination of the previous one?

In my experience, the average Cuban I met appeared significantly happier. Their expressive ways of communication and genuine smiles stood out. Many Westerners tend to frown upon less economically developed countries, pitying them for their perceived poverty and lack of material possessions. Ironically, from their high-horse of superiority, they miss out on the simple luxury that the average Cuban enjoys—a meal shared with family and sometimes even larger communities.

Family Portraits

An attempt to document each meal with our family.

Several delicious meals including Cuban- style chicken sushi.

Group photo with Javi.

Intertwine the Swine

Viñales, Pinar del Río Province, Cuba

Two men add a chain cuff to the hoof of a squealing pig by a roadside fruit stand.

Dinner’s Contemplation

The chained pig stares at its soon-to-be fate on a spit.

Our bus brought us to the top of a hill for zip-lining in Viñales. Surrounded by the fresh air, I initially felt disappointed as the tranquility of the countryside and people-watching captivated me. While waiting for the zip-lining activity, I explored the surroundings and witnessed a farrier caring for a horse’s hooves and a schoolgirl walking along the asphalt road in her uniform. Following a loud squeal, I discovered two men attempting to tether a little orange pig near a fruit cart. The pig was then picked up by its hind leg, held upside down with just one hand by a man in a white shirt. I asked if I could take a picture with the pig and they gestured that I could. The pig stood in front of a large pit coated with ashes and adjacent to long charred sticks, and I recognized this scene. The pig was destined to be dinner, chained in front of the pit where a spit or oven was likely to be placed. Lechon asado is a popular dish in Cuba, where a pig is slowly roasted on a large bamboo stake turned over flames or baked in the ground for 8 to 9 hours. The result is a tender, flavorful, juicy dish with crispy skin, drippings, and lots of chicharron to go around.

I regret not inquiring more about the preparation the men were planning to undertake. A dish like lechon demands time and patience; it is definitely not an instant process. This serves as another illustration of the slow, intentional food preparation deeply ingrained in Cuban cuisine. While rural life offers fewer convenient, instant food options compared to metropolitan areas, likely due to limited access to refrigeration, minimal industrialization, and fewer tourists, it showcases the authenticity of the culinary practices.

Witnessing the precursor to animal butchering and processing in the countryside had me thinking. Although food processing factories exist on the island, particularly in tourist-heavy metropolitan areas like Havana, much of Cuba does not have the readily accessible prepackaged meat in plastic styrofoam trays (as we are accustomed to in the States). In rural areas, roaming chickens, pigs, and goats are freshly butchered when needed by the community. The necessity to butcher whole animals with limited shelf life explains the prevalence of large communal gatherings for meals and the collaborative efforts within the community to prepare these shared meals.

170 CUP Cerveza

Two men tend to their roadside stand hanging and selling bananas on a line tied between two trees. A handmade sign advertises one beer for 170 Cuban pesos. While we were there the official exchange rate was 160 CUP for 1 USD, meaning ~ 1 dollar beer.

Jugo Fresco

Sweet Treats

Many of the desserts and sweet foods are similar to other Latin American countries– topped with cheese. Fidel Castro was also known for instilling an ice cream culture. To this day, the popular ice cream parlor, Coppelia, remains open.

Soul-searching for street food

La Habana Vieja, Cuba

MARKET

MARKET

MARKET

MARKET

MARKET

While roaming through La Habana Vieja during our free time, we set out in search of street food. Apart from the roadside stand in Pinar del Río, vendors selling fried dough from boxes strapped around their necks, and the bodegita on our street, street food options were limited. Exploring the most tourist-packed square in the city, besides Plaza de la Revolución, proved less than ideal. Greeters persistently attempted to lure us into their restaurants, presenting menus with prices significantly higher than what we had grown accustomed to throughout most of the trip.One of our students, proficient in translation, asked locals for recommendations on where to find a bodega where they themselves dined. To our dismay, they only pointed back to the square filled with tourist-targeted restaurants before asking us if we wanted to exchange money. In our pursuit of authentic, locally-appreciated street food, we wandered into an indoor-outdoor fruit and vegetable market.

Tamales to the rescue

We stumbled upon street food in the Plaza de San Francisco de Asís. Interestingly, only locals were approaching the metal cart adjacent to an outdoor grill emitting the enticing aroma of cooked chicken. The menu featured just one type of tamal, but the prospect of trying a local favorite left me perfectly content.

Unlike the Mexican tamales of my Angeleno childhood, this tamal was a steamed block of masa skillfully cut by a boy wearing a backpack and one glove. He adorned the corn with an array of sauces, vegetables, and herbs, presenting a cup with a crunchy topping—later revealed to be a kind of roasted bread and chicarrón. The tamale itself was warm, complemented by the cold, pickled toppings, and flavored by a flavorful spiced sauce.

This experience prompted reflection on the limited street food vendors and fast foodI had encountered. While private businesses are gaining popularity in Cuba, it seems that food vendors may be subject to regulation or not entirely ingrained in the cultural norm. Cuba exhibits faint reminders of cultural elements found in other Latin American countries, yet its current government and history distinctly set the country apart from certain cultural practices you might expect of a Latin American country.

Old Clothes & Ropa Vieja

Ropa vieja, translates to “old clothes.” Prior to my trip, the dish was my favorite Cuban meal. The stewed meat earns its name from its shredded appearance resembling worn fabric.

Throughout our stay, we enjoyed breakfasts and dinners with our host families, savoring the homely atmosphere. For lunches, we explored various privately-owned eateries, discovering unique flavors. One memorable experience had me enjoying my favorite Cuban dish, ropa vieja, on the rooftop of an upscale restaurant with a breathtaking view of Havana. Although the food was impeccably plated and delicious, this fine-dining experience felt somewhat distant from the warmth of sharing meals with my host family. How can you make a dish called “old clothes” fancy?

Being in one of Havana’s most expensive areas, if not the entire country, I recognized that such experiences were likely reserved for the wealthier few—myself included, as a tourist. As a traveler with a strong currency, navigating what is readily available versus what is typical for locals became a nuanced challenge, displaying the complexities of experiencing a culture through a visitor’s lens.

Moros y Cristianos- Black & White

At nearly every meal, one can encounter the bittersweet harmony of “Moros y Cristianos,” which translates to “Moors and Christians.” The perfect congrí of black beans and white rice on the plate not only delights the palate but also serves as a metaphor for Cuba’s complex sociopolitical landscape—a nation intricately woven with black and white threads.

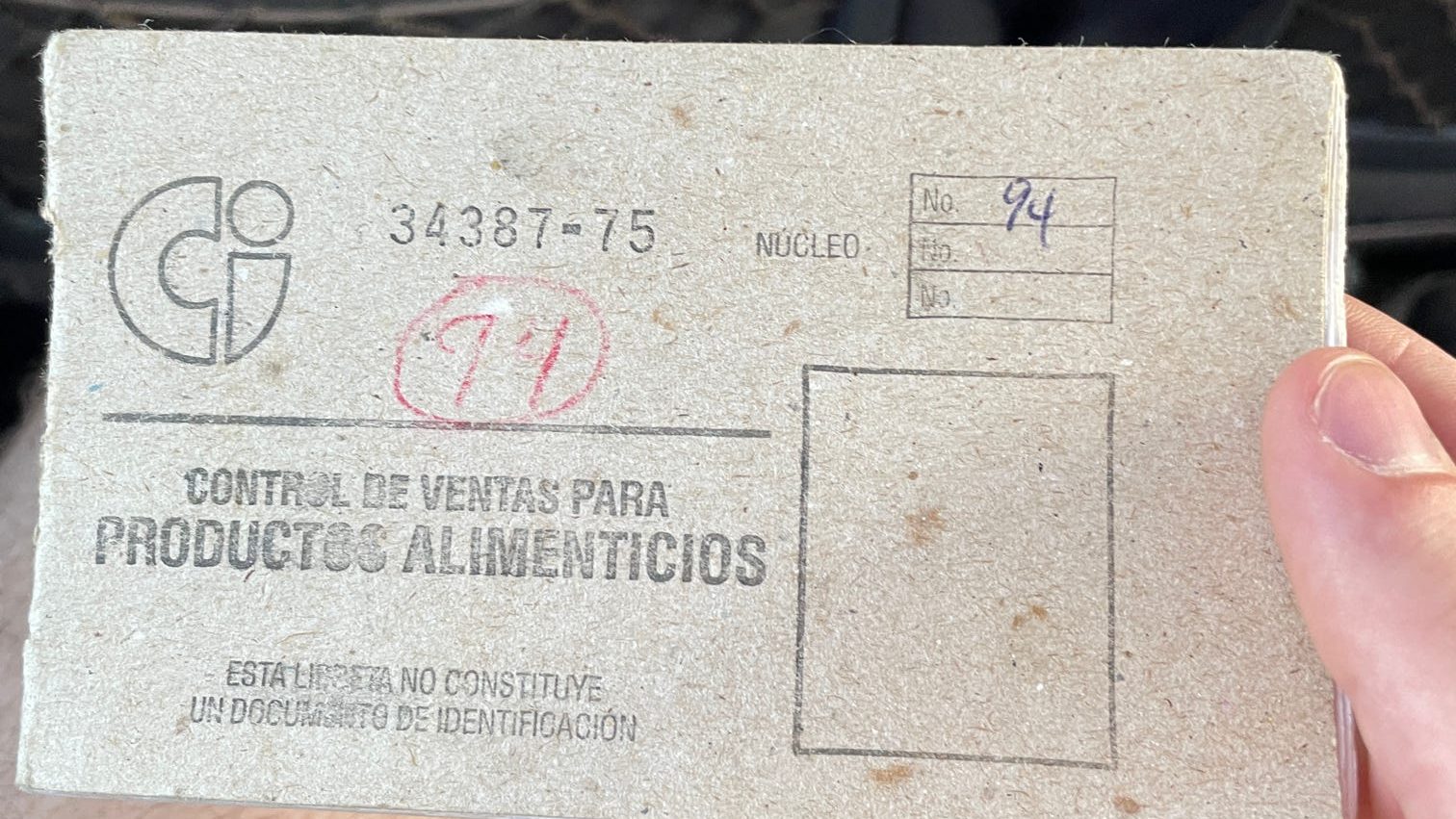

Supplies Booklet

Used for keeping track of monthly rations.

Due to food rationing and the US embargo, repetition is prevalent in Cuban cuisine, with dishes like this one emerging as staples out of necessity. Everyone is allotted a certain amount of beans, rice, meat, oil, coffee, etc., per month, creating a culinary canvas where the black and white symbolism extends beyond the plate. This repetition reflects both the resilience of the Cuban people and the realities of economic challenges.

Savoring the culinary delights shaped by rationing, the black beans and rice take on a dual symbolism. They mirror the resourcefulness of Cuban cooks, yet also echo the disparities faced by citizens in securing basic necessities—a stark contrast against the flavorful resilience in Cuban cuisine.

El Fin.

From the streets of Habana Vieja to the hills of Viñales, each culinary encounter I had displayed a connection between food, community, and celebration. This gastronomic journey, infused with the slow-eating culture, has offered a visual glimpse into sociopolitical influences and internal disparities, illuminating not only the contrasts between the United States and Cuba but also within the intricate fabric of Cuban life.